The consumption pattern

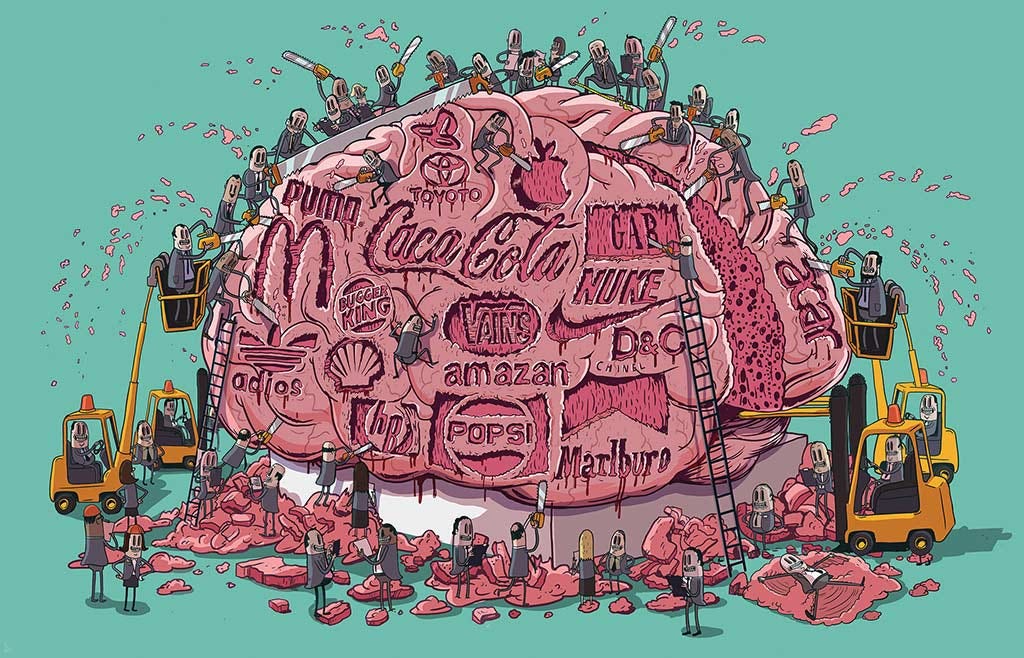

The consumption pattern In the modern era, the capitalist system, like an inexorable machine, has standardized consumption, compelling individuals to follow a universal and homogeneous mould. Under the yoke of capitalism, goods have become not only products of necessity, but also symbols of status and conformity, obliterating the uniqueness and diversity that once made up people’s traditional identities. Standardized consumption essentially promotes the standardization of customs and values, insidiously replacing ancestral practices with habits dictated by a global market. Local traditions, those that have sustained communities over the centuries, end up fading in the face of the advance of consumer culture, which imposes a global monoculture of products and services. This phenomenon kills traditional identities, which are suffocated by the incessant pressure to adhere to what is new and popular, to the detriment of what is old and authentic. Communities, once robust in their peculiarities and rites, are now driven to adopt a way of life that mirrors the capitalist ideal of continuous and unbridled consumption. The damaging effect of this is the dilution of traditional heritage and the fraying of community ties, replaced by an ephemeral and superficial communion of consumers. Capitalism, then, in its incessant quest for the constant accumulation of capital, profit and expansion, fosters the disintegration of traditions and identities, condemning them to oblivion in favor of an illusory and volatile modernity. Let’s take a look at a practical and unsurprising example of how the standardization of consumption by capitalism unfolds in all parts of the world. Nowadays, someone from Beijing or Berlin dresses in practically the same style as someone from Rio de Janeiro or a man from San Diego. Clothing, once marked by the cultural particularities of each region, has been standardized by global brands that dictate trends and fads, thus erasing traditional distinctions. This standardization manifests itself not only in dress, but also in the consumption of products, music and the arts. An individual, whether Chinese, German, Brazilian or American, is now exposed to and inclined to consume the same products – be they technological, food or entertainment – that are promoted by transnational commercial behemoths. Local flavors, the typical delicacies of each land, are supplanted by fast food chains and industrialized foods that offer a homogeneous and global menu. Music and art, the ultimate expressions of a people’s culture and identity, have also suffered from this unification. The songs you hear on the radio in Berlin are the same ones that echo through the streets of Rio de Janeiro, and the art that adorns galleries in Beijing is dictated by a global market that imposes its tastes and preferences. Local and traditional music, art that speaks to the soul of each people, is often relegated to oblivion, buried under the weight of what is widely promoted and marketed. We find ourselves entangled in a web of standardized consumption that murders traditional identities, replacing the rich tapestry of cultural diversity with a monochrome, uniform fabric. In its usurious grip, the socio-economic dynamic under the reins of the Goldene Internationale has forged a world where cultural differences are blurred and the identity of each people is sacrificed on the altar of global consumption. This is the origin of the globalization of world capitalism, which, consequently, is a world without a homeland or a nation. It is therefore essential to recognize the intrinsic value of traditional identities and fight for their preservation in the face of the overwhelming power of standardized consumption. Only in this way can we ensure that the cultural riches and memories of peoples are not obliterated by an economy that, at its core, values profit (the cult of Mammon) more than the lives of workers and the peoples of the world. An Alle, Alle! Author of the post schokoladenbaron von Schwarzwald Editor of aristocraticsocialism.com

What is mammonism?

What is mammonism? Capitalism, since its consolidation through the Industrial Revolution, has not only introduced a new economic, social, political form or the like into our society, but it has introduced something that is above all of these, and that is essentially subordinated to what has been mentioned, and that is — a new spirit. Every human organization, whether it’s a complex society, a tribal society, or a simple neighborhood or street organization, is guided by a spirit that directs the entire functioning of that human organization, and that spirit is the higher ideas that act upon the organization, which can be dispersed and chaotic ideas or ideas consolidated into a single body, such as a worldview or simply a doctrine. Every person or civilization is guided by a spirit of their époque, which underlies all the actions and measures taken by a human organization, which takes certain measures in view of a set of higher thoughts that order its actions and Being in certain situations of time and space. Nothing could be different when we talk about capitalism, which is no exception to what has been said so far, dear reader. We have observed that much has been said about capitalism from countless perspectives and sides, mainly – given the nature of the thing – from the economic side, but much has been ignored by those who analyze capitalism purely in this way (emphasis on the “purely”), that the economic side is only one of the sides of this system that is in force and governs our entire economic, social and, above all, ethical and moral functioning. In fact, since its emergence, capitalism has brought with it a new spirit and all the consequences of capitalism are ultimately derived from this spirit. This spirit is responsible for the essence of capitalism, from which everything else is derived, and is the basis on which the capitalist method of production functions, that is, the accumulation of capital, which we can translate as producing and acting with the aim of maximizing capital in its constant dynamic of self-valorization. If the spirit of socialism in general (regardless of its type) is the spirit of communitarianism, mutualism and voluntary solidarity, the capitalist spirit, on the other hand, is not only individualistic and materialistic, but above all mammonistic. And what do we understand and define by “mammonism”? To repeat the words of the founder of our worldview, Gottfried Feder, Mammonism is “[…] a mentality that has seized the widest circle of peoples; the insatiable desire for profit, the purely worldly orientation of the concept of life, which has already led to a frightening decline of all moral concepts and must continue to do so” [1], and Mammonism manifests itself in practice through the “[…] overwhelming internationalism overwhelming international monetary powers supranational financial power enthroned above any right of self-determination of peoples, international big business, or purely Golden International” [2]. The term “Mammonism” comes from “Mammon”, which in turn comes from the Aramaic word “mammon” ( מָמוֹנָא ), meaning “possession” or even “goods”, but it is more commonly used to mean money and wealth and is described in some religious passages, such as Biblical texts in which “Mammon” in such a context would be a god or a demon. For example, we have the following very famous passage from the Bible, from the Gospel of Matthew: No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon. – Matthew 6:24 Other translations of the Bible have simply replaced “Mammon” with “wealth” or even “money. It should be noted, however, that Mammon is not simply the god of money, but the god of the cult of money and wealth in general, and is associated in Christian theology with the sin of greed or avarice (one of the seven deadly sins) in its purest form. Based on this, the term “Mammonism” was created to emphasize the Spirit of Greed, however, we don’t know who was the first user of the term and under what circumstances it was first used, what we do know so far is that its use was quite common on the part of some 19th century authors, such as the Scottish essayist and philosopher Thomas Carlyle in his literary essay “Past and Present” originally published in England in 1843 and later in the United States. Among other things, he explained Mammonism as follows[3]: “Yes, O Sauerteig, it is very singular. If we do not ‘succeed,’ where is the use of us? We had better never have been born. “Tremble intensely,” as our friend the Emperor of China says: there is the black Bottomless of Terror; what Sauerteig calls the ‘Hell of the English!’-But indeed this Hell belongs naturally to the Gospel of Mammonism, which also has its corresponding Heaven. For there is one Reality among so many Phantasms; about one thing we are entirely in earnest: The making of money. Working Mammonism does divide the world with idle game-preserving Dilettantism: — thank Heaven that there is even Mammonism, anything we are in earnest about! Idleness is worst, Idleness alone is without hope: work earnestly at anything, you will by degrees learn to work at almost all things. There is endless hope in work, where it even works at making money.” Furthermore, the term “Mammonism” can be found in numerous other works and writings from the 19th century, including a work by James Glentworth Butler on the Old Testament[4]: “The perils of mammonism threaten those who make little money as well as those who make much money. The spirit which leads to over-value and over-love of money is independent of amount. Safety lies in placing one’s self in a right moral relation to money. The man who feels himself drifting on to the quicksands of mammonism will find an anchor, sure and steadfast, in cheerful and prompt obedience to the apostolic